Over the past year, the use of the words “stretch”, “lengthened partials”, and “longer-muscle lengths” has taken over the fitness space.

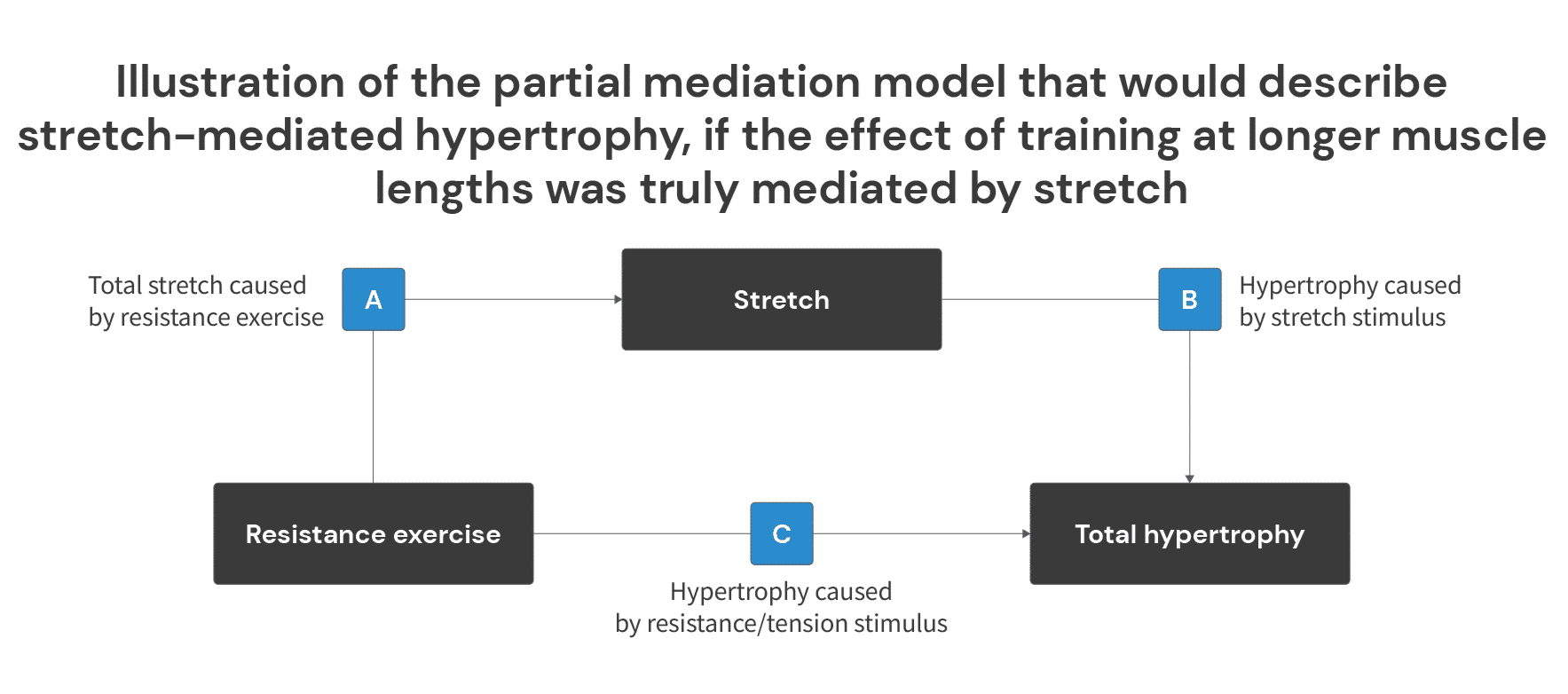

Chief among them has been the expression “stretch-mediated hypertrophy”, used to describe the additional muscle growth observed from using lengthened partials, or focusing on the stretch during resistance training.

However, we’re here to set the record straight. We’ve previously written about why Lengthened Partials Probably Do Not Cause Stretch-Mediated Hypertrophy.

There has recently been a renaissance in the research on lengthened training for muscle hypertrophy (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). We’re seeing more studies than ever before, most of which find slightly greater muscle growth from focusing on the stretched position of the exercise, whether by the use of lengthened partial repetitions, lengthened partials after hitting failure, or simply picking an exercise that places a greater loaded stretch on the target muscle.

Stretch-mediated hypertrophy, on the other hand, has been around for quite some time. The first research demonstrating insane muscle growth from stretching was conducted in the 1970s and had its start in animal models.

A classic example of such a study was conducted by Sola and colleagues in 1973. 100g and 200g weights were attached to the wings of chickens to induce stretch-mediated hypertrophy of latissimus dorsi and teres minor muscles, with the other wing serving as a control group. Dramatic hypertrophy of the lat muscle being stretched was observed, with an increase in muscle weight of up to ~170% being observed. Importantly, Sola examined muscle hypertrophy resulting from this stretching intervention in both innervated and denervated muscles (i.e. supplied with nerves or not). Since only innervated muscle can actively contract, this study provides an estimate of how much hypertrophy is truly stretch-mediated versus mediated by active contraction under load.

Many subsequent studies were conducted in animals, replicating the same finding over and over again: substantial muscle growth purely from stretching a muscle, usually with very high loads, and, even more saliently, for exceedingly long durations, often multiple hours a day or even 24/7. This area of research is where the term stretch-mediated hypertrophy occurred.

Today, the term is being used to describe the additional hypertrophy observed from resistance training with a slight emphasis on the lengthened position. To be clear, in contrast to seminal animal studies, many current studies have human participants spend an extra minute or two per workout in the lengthened position.

As an example, Pedrosa and colleagues observed approximately twice as much quad hypertrophy when training knee extensions through a range of 65-100° of knee flexion versus 30-65° of knee flexion. However, doing some napkin-math, the participants spent only an extra two minutes or so per week at longer-muscle lengths in the lengthened partial group. What’s more, their quads weren’t even particularly stretched, since we’re capable of around 150 degrees of knee flexion, meaning the participants were missing 50 degrees of additional quad stretch.

This example is illustrative of the literature at-large. To be clear, stretch-mediated hypertrophy can occur in humans; but, it usually requires interventions lasting >1 hour per day, at high discomfort ratings. The duration and intensity of stretching in the lengthened resistance training literature simply aren’t sufficient to induce stretch-mediated hypertrophy. Rather, we’re likely dealing with a different, unexplained phenomenon.

Another common claim is that lengthened training works through stretch-mediated hypertrophy, and that stretch-mediated hypertrophy only causes more growth through the addition of sarcomeres-in-series. Since the addition of sarcomeres-in-series is a finite process, there is a finite benefit: only beginners see a benefit, for up to a few months.

There is some support in the scientific literature for the idea that lengthened training may increase fascicle length in humans (and increases in fascicle length are assumed to reflect an increase in sarcomeres-in-series). However, the research on true stretch-mediated hypertrophy doesn’t suggest that it only increases muscle size due to the addition of sarcomeres in series. Rather, extremely robust increases in fiber cross-sectional area are also observed.

So, a) if lengthened resistance training does cause increase in sarcomeres-in-series, that in no way precludes the possibility that it also leads to larger increases in fiber cross-sectional area as well, and b) even if lengthened training and stretch-mediated hypertrophy did work via the same mechanism, that also wouldn’t imply that all of the additional gains were due to an increase in sarcomeres-in-series, because “true” stretch-mediated hypertrophy does also cause very robust gains in fiber cross-sectional area.

In essence, the assumption the lengthened training only “works” for beginners is based on a pretty serious misunderstanding of the stretch-mediated hypertrophy literature, compounded by the premature (and likely erroneous) assumption that lengthened resistance training and stretch-mediated hypertrophy are synonymous and work via identical mechanisms.

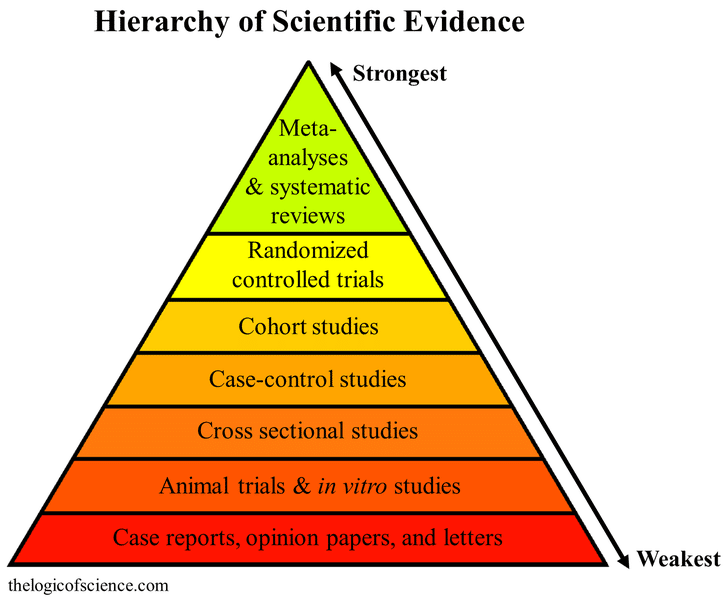

If you buy into these ideas, and you’ve been training for a little while, you’ll dismiss the idea of lengthened training being beneficial for muscle growth. And yet, the vast majority of the studies on the topic do find greater muscle growth from lengthened training. In relation to the hierarchy of evidence, multiple randomized controlled trials in humans form a much stronger evidentiary basis than a series of assumptions predicated on the false equivalency that lengthened training induces stretch-mediated hypertrophy.

Hopefully, this newsletter has helped you understand why stretch-mediated hypertrophy is overhyped, and a misnomer when it comes to the current research into lengthened training for muscle hypertrophy. If you’d like to read more on this topic, check out our full-length article on the topic.